A multiracial Hawaii

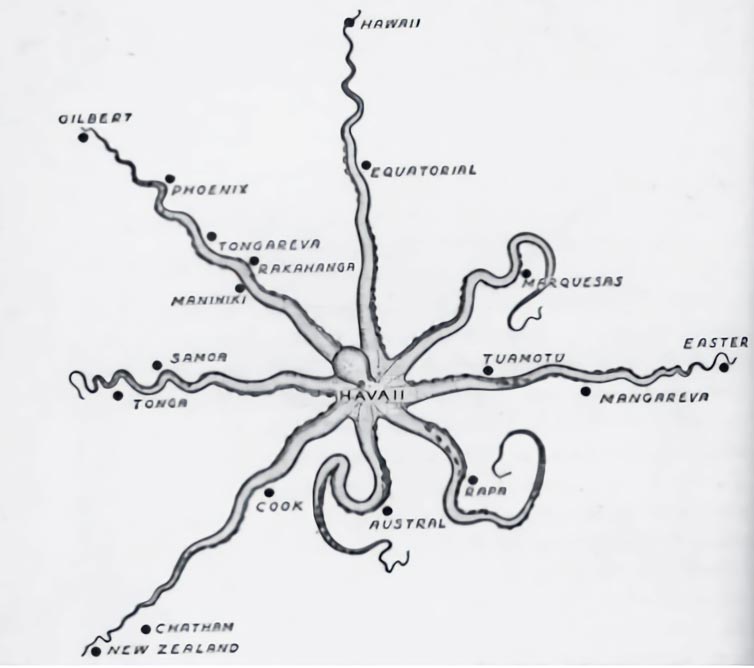

Hawaii has long been a potluck society, in that it hosts communal gatherings where each guest comes from somewhere else. Although not all guests were welcomed or invited, the identities they’ve brought contributed to the mixed plates around the table.

The multiracial experience is unique in Hawaii compared to other metropolises such as Los Angeles, Houston and New York because the influx of diverse populations was concentrated on islands totaling 6,423.4 square miles in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Colonization, annexation and immigration became the driving forces for racial and ethnic change throughout Hawaii’s history. When Captain James Cook first arrived in Hawaii in 1778, an estimated 683,000 native Hawaiians were inhabiting the islands. The Englishmen brought along foreign diseases such as measles, smallpox and tuberculosis that swiftly killed native Hawaiians. By 1800, the population had declined by 48%.

Eliot Elisofon/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

The contemporary consensus is that race is a social construct, not a biological attribute. Scientists say that the human species is so evolutionarily young and it’s migrator patterns so wide that “it has not had the chance to divide itself into separate biological groups or ‘races’ in any but the most superficial of ways Do Races Differ? Not Really, Genes Show.” In Hawai’i, people have preferred to use the term “ancestry” to describe human diversity. “Ancestry reflects the fact that human variations do have a connection to the geographical origins of our ancestors, National Library of Medicine.”

Immigration, Colonization and Annexation

In the early 1800’s the sugar industry grew so much that white plantation owners began importing contracted laborers from China. The first 175 Chinese field workers arrived in 1852 and were bound to a five year contract in which they were paid $3 per month. After finishing their contracts, the majority of immigrants decided to raise their families in Hawaii and moved to more urban areas like Honolulu to open businesses. Honolulu’s Chinatown became one of many residential enclaves throughout O’ahu.

In 1878, the first Portuguese laborers from Madeira, the Azores and mainland Portugal arrived with their families. They were offered superior contracts compared to their Asian counterparts who were forced to leave their families behind. Many portuguese went on to start restaurant businesses or farms after completing their contracts. Their cuisine is sprinkled across all the islands, with many comfort-food restaurants listing Portuguese bean soup on their menus.

After Congress passed the first Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, limiting Chinese immigration, the Kingdom imported Japanese plantation laborers beginning 1885. Their arrivals abruptly stopped in 1924 when the Federal Immigration Act was passed which is why the Japanese were defined by generation in Hawaii.

Korean plantation workers arrived in 1903 and the first Filipino plantation laborers arrived on the Big Island in 1906.

In 2022, the World Population Review ranked Hawaii as, “the most racially and ethnically diverse state in the U.S. with about 38.6% of the population being Asian, 24.7% white, 10% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 1.6% Black, 0.3% American Indian and Alaska Native, and 23.6% being multi-ethnic.”

Even individuals mixed with the same ethnic ingredients have different experiences due to the extent they do, see and feel things through a conscious lens of their multiraciality. Because these experiences are lived with such diverse perceptions, the sense of relatedness spans wider across relationships with many ethnic groups.

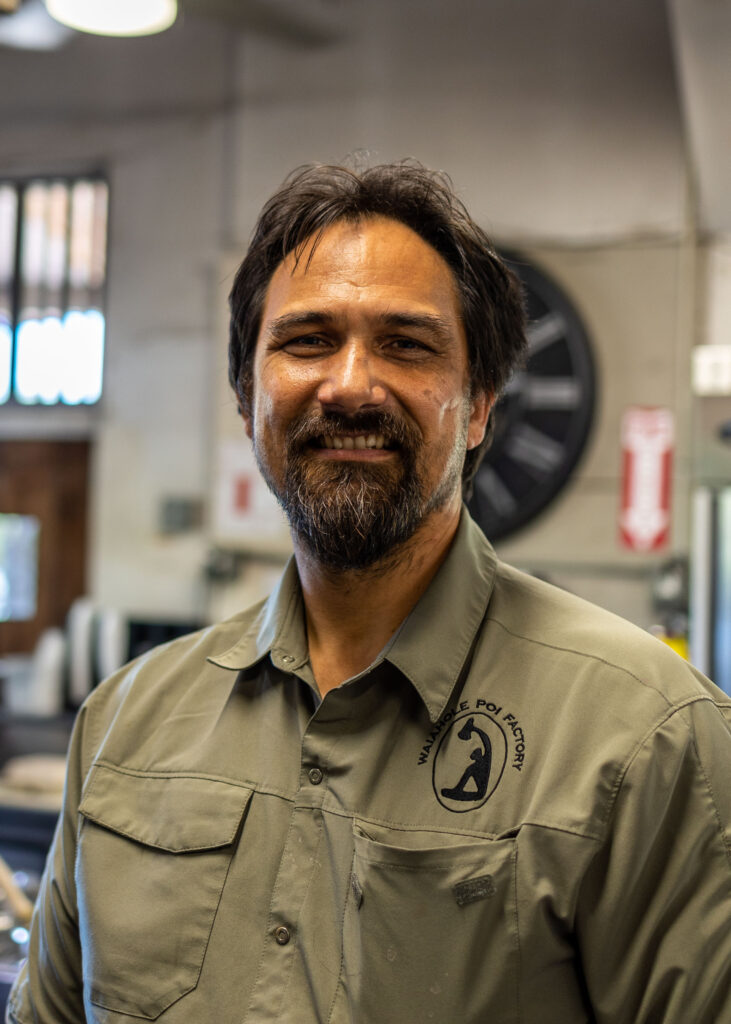

Keliko Hoe

To Liko Hoe, Hakipu’u resident and third generation owner of the Waiahole Poi Factory, the multiracial identity is ultimately just identity. “Even a family of the same race is going to be a mixture of different cultures,” said Hoe. “My mom, who is from South Dakota, is a mixture of people who spoke different languages from across Europe.”

When Hoe was just 5 or 6 years old, his parents would craft traditional Hawaiian instruments and sell them at craft fairs and hula functions. One of the goals of Hoe’s family was to bring Hawaiian arts and perspectives into a more solid foundation — a physical structure. At that time, few Hawaiians spoke their native language, but you could find Hawaiian culture in the form of music and chants. In the 1970’s, there was a resurgence of interest in Hawaiian art and hula.

In 1971 the poi factory closed after running for 70 years which led to Hoe’s parents deciding to buy the property and turn it into an art gallery. By facilitating a space for communities to connect with their heritage, Hoe’s family helped others reconnect and communicate with their kupuna, or ancestors.

After a decade of running the gallery, Hoe’s family transformed the gallery back into a factory to fuse another core value, not necessarily unique to Hawaiian culture: family.

However, the concept of family in Hawaii is a lot more inclusive than individuals who are related by blood, marriage, or adopted who live together. People in Hawaii use the term hanai to describe those they informally adopt into their families. They take care of their hanai family the same way they would a blood related loved one. People with multiracial identities in Hawaii can straddle between groups such as friendships, family relationships and neighborhoods where many of these relationships overlap.

hanai – foster child, adopted child; to raise, rear, feed, nourish, sustain; provider, caretaker.

“Most families’ core values are going to be the same. It’s not just Hawaiian.” Hoe doesn’t think consciously about having relationships with those of other races, but he does think it’s important to maintain a connection with family.

For 20 years the non-profit incubator kitchen invited local families from Waiahole, Waikane and Hakipu’u to rent out the space to experiment with cooking new foods. In 2009, the Hoes turned the factory back into a full time homemade Hawaiian food restaurant that Liko slowly started to take over.

Hoe serves authentic Hawaiian food alongside 30 other workers, a good chunk of them being his cousins.

Hoe has lived in Hakipu’u all his life. In fact, he lives about 300 feet from his childhood home, on property that belonged to his great grandfather and used to be lo’i land. Hoe feels he is fortunate to grow up in a community where a lot of his neighbors were family. “There’s a good chance that if you are from there, you are related,” said Hoe. The compound he grew up in was the gathering place even for his family that did not live in Hakipu’u.

In a traditional Hawaiian context, living in a home that has been with your family for generations is typical, but today, that is the exception. “Unfortunately many people don’t have a connection to the place they live and where their ancestors came,” said Hoe. “That is the core of a lot of tension in Hawaii; displacement.”

“Lately, a lot of visitors have been extractive and have taken our beaches, land and culture to profit and bring the benefits back with them,” said Hoe. While tourism makes up 21% of the state’s economy, Hoe still hopes to see an 80% drop in the tourists numbers and an increase in several thousands of local and Hawaiian owned businesses. “That’s what the poi factory is,” said Hoe. “We are the ones hosting the visitors, at least for lunch.”

To Hoe, the main part of hosting others is feeding them. Having a deep connection to the place his Hawaiian family came from has allowed Hoe to extend his hospitality to his greater local, national and international community. “My goal is to be someplace that anybody could come to and I feel that it is important that the food we serve is the actual food of our community.” Since the poi factory is on the outside of town, locals visit when they are off work or over the weekend, while tourists make up a bigger population of its visitors.

“We’ve been able to create community by actual interactions and integration of people and cultures.” Hoe pounds poi outside of the factory with his son and daughter on Sundays and Wednesdays to invite those interactions. The poi factory not only provides the opportunity for visitors to try a traditional food, but also learn how it is made and its history. “That’s what I want to do when I travel. I’d rather go to the place that fully embodies Hawaii.”

Hoe seizes any opportunity to “talk story” with visitors and hear a little bit of perspective. “Once this older Filipino lady said that the men where she comes from used to pound the banana in the way the Hawaiians pound poi. She said it was like candy and they would take it to the girls they were interested in,” said Hoe. “Food holds a lot. It can tell you about a mixture of cultures and its environment.”

To Hoe the multiracial identity is ultimately just identity. “Even a family of the same race is going to be a mixture of different cultures,” said Hoe. “My mom, who is from South Dakota, is a mixture of people who spoke different languages from across Europe.”

“When you stop to think about it, or whether or not you stop to think about it, those people are who you are. I feel that it is a rich thing to be connected to a big part of the world. The more understanding we have of our history, the more understanding we have of ourselves. Then we can ask what we want to do now and what impact am I going to try to make or not.”

“It’s important to recognize all the parts of who you are. It becomes a little problematic when you recognize one and disregard the other and for good reason — nobody wants to be disregarded.”

Cris and Emilie Stickley

Cris and Emilie Stickley decided to stay on Oahu after their destination wedding in May of 2005. Emilie was working at Tripler Army Medical Center while Cris was working toward his PhD in kinesiology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. After leaving briefly for Emilie’s first duty station in Colorado, the couple returned to start their family and build a home.

The couple from Ohio wanted their children to be a part of the aunty and uncle community in Hawaii. “Having a name of respect to call your elders that’s also family is so different than anywhere else in the United States,” said Emilie. “There’s Ms. Mrs. and Mr. but here, the respect term is also a family term which speaks to what community is for children here.”

In 2007, Cris and Emilie adopted their daughter Juneau from Vietnam. At the same time, they were pregnant with their daughter Nova.

“When we decided to adopt and have an interracial family, we felt like here, no one even looks twice at your kid who doesn’t look like you,” shared Emilie. “Then when we go back to Ohio and are walking around as a family with all this diversity, people are clearly trying to figure it out. They stare at us when we walk places and we forget that that’s how the rest of the world looks. It always felt natural to be here and realize this is how families are in Hawaii — the kids and the parents don’t look the same half the time and no one asks questions about that. It just felt comfortable for us.”

Cris and Emilie had their third child, Jude, in 2008.

By the time they wanted to adopt again, they were both over 30 years old and married longer, qualifying them to adopt Justis through a special needs program in China.

Their sons don’t wonder why they don’t look alike because they watch Juneau and Justis’ adoption story at least once a year. “The boys feel they are identical twins,” said Cris. “The case with our family is that it’s not about where you came from but rather where you go,” said Cris. “What matters is what happens as part of a family.”

Being adopted is not part of the identity their children play up to the rest of the world, but Cris and Emilie have met a lot of parents through the adoption community that give a lot more attention to where their kids are from than they do. They believe it might be because they are surrounded and immersed in a different cultural environment than they are.

The Stickley family now lives on a farm in Hilo. Nova attends Waiakea High School while Juneau, Jude and Justis do homeschool through Harmony Educational Services.

“The Big Island, Hilo in particular, has a small town feel that’s like where we each grew up, where everybody knew everybody. I feel like in this setting, even when you’re out, regardless of your race, it’s obvious if you’re a tourist or not. If it’s obvious you’re not a tourist, there’s enough of a small town where the same restaurants will know you unlike even in Honolulu where there are so many people that even if you periodically went into the same restaurants, they may not recognize you.”

It’s important to people in Hilo to know who their community members are. “It feels like everybody’s first priority is knowing ‘are you part of my community’,” said Cris. “Not, ‘are you part of my race?’”

Cris and Emilie feel they are in a unique position that gives them an advantage with their interactions in a multiracial environment compared to other Caucasian people who come to Hawaii. “We have something to bring to the people of Hawaii by being in education and medicine,” said Emilie. “We’re not here to take something from this beautiful place where we’re living, but we’re here bringing something which feels really good as the giver, but also as the receiver.” They feel their experience may be a little protected in that way.

Up until last year, Emilie had not personally experienced a situation in which she was discriminated against for her race. They started fostering kids from a local family that were too young to speak. “When the little boy started talking, he called Cris ‘dad’ and me ‘mom’ because he hadn’t learned words yet and he lives with us where everybody else is calling us mom and dad,” explained Emilie.

When the kids would go back to their mom, she would call Cris and Emilie names and use racial slurs out of bitterness. “That was very very hurtful because that is a bridge we cannot cross — her kids were taken from her and were put with a haole family who I’m sure she feels is not raising them with the same values that she thinks are part of her Hawaiian culture,” said Emilie. “I think it’s because now we were not bringing something but were taking something, her family, not intentionally but that is how she sees it.”

The Stickleys recognize that their multiracial interactions might look different if they lived in Puna or Pahoa, or if they sent Nova to Hilo High School instead of Waiakea High School. At Hilo High School, the student demographics are dominated by local native Hawaiians, making Hawaiian pride among youth more pronounced than it is at Waiakea. Waiakea High School, just outside of the Hilo public school district, is more of a blend of locals and non locals, Asians, Caucasians, and students of more than one race. Pahoa and Puna have a higher poverty rate of 29.7% compared to 17% in Hilo as well as a higher native Hawaiian population. “There would be some financial discrepancy between the way they live and the way they live and that could create animosity,” said Emilie.

They also know white people who live down Pahoa way who are up to their ears in that community. “What I experience is that people don’t like when outsiders try to act as if they know better because they’re from the mainland, but if you’re part of a community, that’s what people value here,” said Cris.

“I find myself annoyed when people visit and don’t get how Hawaii works,” shared Emilie. “You can’t be rude even if something is going wrong. Even if a line is long, you just can’t get frustrated here,” said Emilie. “I notice the things we’ve adapted to over the last 17 years such as saying hello to those you make eye contact with.” Cris and Emilie have friends from Europe and the US mainland who have been living in Hawaii longer but have either not adapted to the unique culture in Hawaii or do not embrace it in the ways they have.

Emilie thinks it’s important to have relationships with those of other races. “I’ve been remarking on how I’ve never been able to have what I feel is a really close genuine friendship with a local Hawaiian woman,” she said. “It’s something I’ve worked for but I haven’t figured out how it works even after having lived here for almost twenty years.”

To Cris, it’s not important or unimportant. “It doesn’t register on my radar to develop relationships with those in other ethnic groups,” he said. “We’re either going to be compatible and share values or we’re not.” Either way, the state fosters multiracial interactions because of the baseline cultural diversity. By vicinity and volume, Hawaii facilitates opportunities for everyone to become multicultural.

Within Cris’ job, many of the students and faculty come from pacific rim Japan, China, Korea. That is something you get in Hawaii. “If I were at Ohio State in my exact same job, the makeup of the community wouldn’t create situations where I’ve got all these students and colleagues from different countries, racial backgrounds and heritages.”

By living in Hawaii, the Stickleys are surrounded by parts of cultures that they’ve naturally integrated as their own. “I’m taking a class at UCSF and when I flew there, of course I took omiyage with me because that’s what you do— you bring something from Hawaii,” shared Emilie. Her professors were surprised because they had never experienced a student gifting them as a way to show gratitude for teaching her class.

Omiyage is a Japanese expression of aloha that directly translates to “souvenir”. Kama’aina have adopted this practice of gift giving as a way of showing gratitude and goodwill.

kama`aina – Native-born, one born in a place, host; native plant; acquainted, familiar, land child.

The local community culture in Hilo is similar to that in Cris and Emilie’s hometowns in that the mindset of binding together as a community to help each other out and to pull together when times are needed holds firm. The difference in both areas’ social interactions is that there is a lack of exposure to cultural diversity, not distinctly racial diversity, in rural and suburban towns in the Midwest.

“Everybody is homogeneously from the same culture which creates more of an awkward confusion, not out of any racial animus or tension, but there is no point of reference to begin to relate to somebody that is from just that different of a culture,” said Cris. With a complete isolation from other cultures, it is hard for anybody who lives in an environment dominated by one culture to accommodate someone of another race who grew up with a different culture.

The Stickleys’ experiences interacting with their multiracial environment are unique because of the way they have openly assimilated to the diverse cultures embraced in Hawaii. “I don’t think our experience is typical,” said Emilie. But as a doctor and professor, foster parents, volunteers, coaches and customers, Cris and Emilie Stickley have expanded their roots as kama’aina, shaping them into noble community members of Hawaii.

Chester Leoso

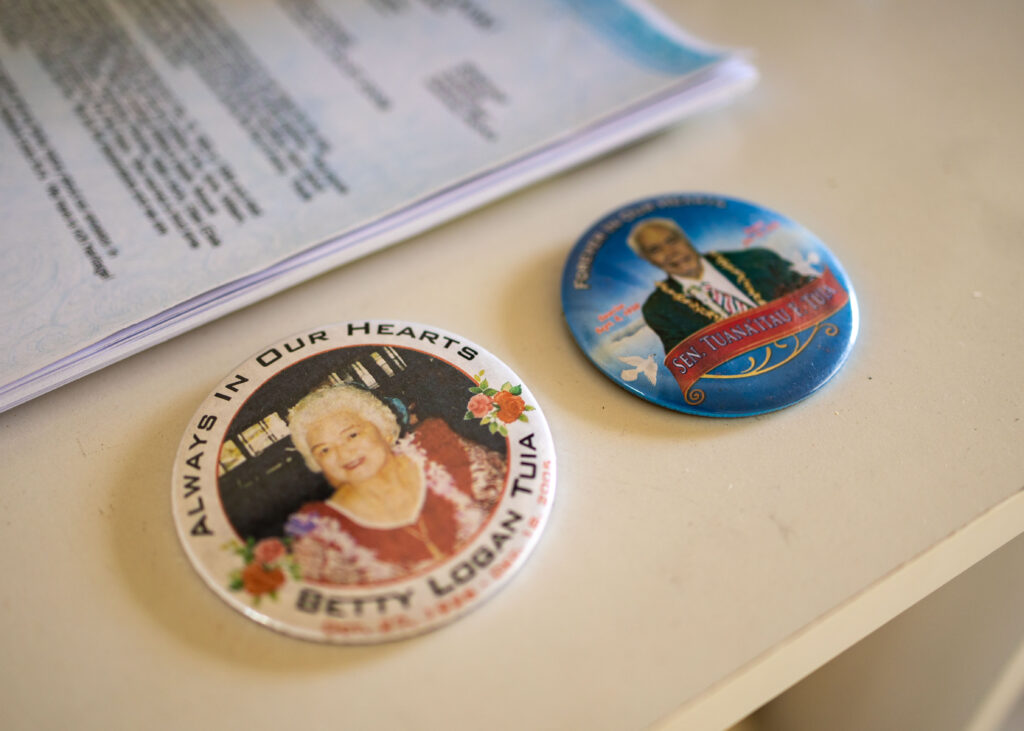

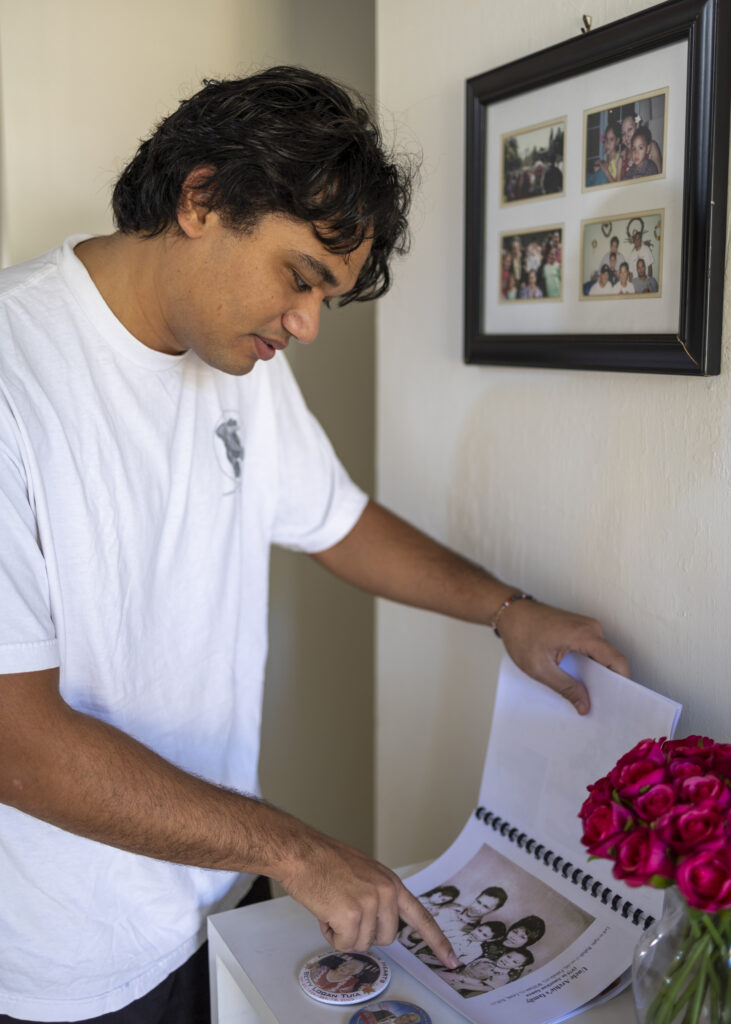

Leoso lives with his mom in Mililani, central of Oahu. On each wall hangs photos of family. “It’s a family’s duty to remember their family,” said Leoso.

Two pins of Leoso’s great grandmother and great grandfather, the longest senator in the history of American Samoa. “After they pass, we wear them and give them out to people,” said Leoso’s mom.

Leoso’s family lives by their culture every single day. “He’s shy and humble about it, which is how it should be,” said Leoso’s mom.

Leoso hangs photos and cards from friends and family in his bedroom.

Leoso shows how to wear a lavalava, a traditional garment worn like a skirt for both sexes in Samoa. “As long as there’s chores to be done, you wear lavalava. Everybody has to be in the same position and know who they belong with,” said Leoso. “It’s meant to be equal.”

Chester Leoso was born in American Samoa in 1998 and moved to Oahu in 2002. Leoso moved on a rush with his mom and older sister after his parents divorced. After living in a place where he only knew what it was like to be part of the majority, Leoso had to quickly adapt to Hawaii’s multiracial environment.

It was a multicultural and multiracial shock. I started to see the ignorance being tested because before, I was comfortable and now I’m the minority. I started to encompass a lot of things about identity. At a young age you have the tendency to belong and you want to attach yourself to people that share similar interests. The one thing I had that other kids didn’t have was that I didn’t grow up here. It was a great experience to know people were very welcoming. But now it’s becoming a little more intense as you grow up in terms of multiraciality and you begin to see groups and clusters form, and the majority is taking a lot of that space.

In middle school, Leoso had to overcome the social ignorance that stemmed from his upbringing where a person’s race did not impact whether or not a relationship would form between two people. Once he could cognitively identify the reason why groups formed, he had to learn what each group’s social standards were.

I noticed as a teen, people started relationships with specific races. I had to ask myself what are the mannerisms, behaviors, structures and prejudice that classify itself as a race, and then look at what I have to compare. I went to extreme means to get that. I was anemic and I noticed the majority of people having relationships were skinny. I lost nearly 80 lbs. and continued to lose weight.

The race he looked to others was different from the race in which he self-identifies. He came to accept that he could not be classified into one group or one identity and for that reason, his relationships would be limited. He felt his multiraciality limited who his partner could be due to the racial disparities he observed. It comes with having multiracial significance in their perspective. He started to observe how others with a multiracial significance in their perspective affected his ability to develop relationships.

Although multiracial myself, the majority of my ethnic upcomings came from only research and history. As far as fitting in, it never came to the point of my race, but rather how I looked as my race. Only on the fundamental level of the observer in the physical plane, which is me and you, where you can see my face and I can see your face — that is what I’m going to base my assumption on. I was limited in my options because of what I observed and also the racial disparities that came with how I looked.

In the analogy of relationships, looking through the lens of race can disparage multiracial people because of how racial dynamics shape social structures, sometimes making them feel limited. Leoso chooses to identify himself by his ethnicities and cultures rather than his race because race is only representative of physical characteristics. While the historical concept of race describes the geographic pattern of genetic variation over time, modern scientists properly describe human diversity with the term “ancestry”.

What makes you different is how you identify with your culture and ethnic background. Race has done nothing except teach me to value others. Chinese and Samoan are two different races, demographics and cultures that for some reason had a union. The beauty in the union itself is the beauty that is multiracial.

From a spiritual perspective, Leoso’s multiracial identity symbolizes two households coming together notwithstanding social epidemic laws that prohibited or loathed those kinds of unions.

A person that is multiracial can define themselves based on who they really are. When you can identify yourself, you have a choice to learn more about those sides of you. The birth of you being multiracial is imperative. It served me in a way that I am part of two different parts of the world. All of that lovely union that made me four generations ago is one of the most epic stories to have been told.

To maintain bloodlines in American Samoa, people were expected to marry other Samoans. Up until two centuries ago, there wasn’t a persistent influx of Europeans to the small island group. Once the amount of missionaries and traders intensified, curiosity curated and social values started to change. Travelers would change the way the islands perceived the world, making them more inviting and competent toward other cultures and races — only on the basis that it served the island.

I connect with my Chinese and Samoan identities through behavior. When I behave in a manner that is culturally significantly similar to Samoans, that is when I align myself majority of the time. There is a mantle of Fa`a Samoa, or “the Samoan way”, that to be of Samoa that is to be respectful. Taking your shoes off was an Asian mannerism that Samoans picked up. Another thing is gift giving. When I act and behave that could be similar to Samoans is when I feel most Samoan. It’s interesting because those behaviors are relatively similar throughout the world. Other traditions that come from being from Samoa stick out. When we look at items such as waste, which is not a thing. Wasting food is not a practice. Even if you don’t like the food, you gotta eat the damn food. It’s about giving thanks to those who fed you regardless of if you’re vegan or not. You eat what’s on the table and you never know when your last meal is going to be. It’s the most polite thing to do.

Hawaii’s isolated geographic location and size along with a high population density of people makes it easy to meet and interact with people of different races and cultures. With visitations alone, tourists from Japan, the U.S. mainland and Canada are constantly penetrating Hawaii.

It’s easy to have a conversation and build a rapport and retain the narrative from these different people. I give major significance to the environment allowing me to make those relationships. If I wasn’t in an environment that didn’t test my ignorance, I wouldn’t have even had the curiosity to want multiracial relationships and even reflect on myself.

May Kamaka

The spirit of aloha is present in 20-year-old hula dancer May Kamaka.

Kamaka grew up as the second oldest of four children in a small house in Kaneohe, a few minutes walk from her grandparent’s and aunt’s houses. She currently resides in Manoa to be closer to the University of Hawaii at Manoa where she is working toward her bachelor’s degree in Hawaiian studies and taking courses to prepare for medical school.

Growing up in Hawaii in a large but tight-knit multiracial family, Kamaka has well established connections to all branches of her identity.

A huge part of being multiracial is being more accepting of and understanding of different cultures. A lot of multiracial people are put in a position where they aren’t really accepted because they aren’t a full something. They have to adapt to each side of their family. With different cultures, there are different standards, physical changes and moral values. Multiracial people are good at adapting to these things because they have the knowledge and experience doing it themselves. This makes them more understanding to others because they know what it’s like.

Consecutive years of experience in a racially diverse environment presents a higher quantity of opportunities to engage a person with perceived discrepancies between their physical traits. People who grow up in Hawaii are naturally conditioned to approach bodies with physical characteristics atypical of any pure race. Monoracial people who are not raised in Hawaii are not exposed to the same melting pot environment.

In terms of my physicality, nobody thinks I am just one race. It’s always, “what are you?” not, “are you this”. I am the only person in my family with light eyes. They’re green. I got them from my great grandfather on my mom’s side who was Filipino and white. A lot of people tell me I am beautiful because of my light eyes, which are usually associated with being white. People who are not from here guess that I am Hawaiian while people from here usually guess that I am white and something else. Even within my family, we look quite different from each other. I don’t think I really look like my parents but my siblings look the most like me.

At Kamaka’s hālau, or school where she practices hula, she learned that some things about cultures are not secret, but are private. She attributes her hospitable qualities to her Hawaiian culture. She likes to share the stories behind her Hawaiian values but couples this with the understanding that some things are only meant to have been learned by the right people — people that would respect and appreciate that culture.

I was raised in a very accepting and loving household from all different ends, my Filipino, Hawaiian and white family. Not a single side of my family is completely one thing. The closest I can get to pure breed is my grandma who is from Germany, and her values were evident in cooking, cleaning and gender roles. I had enough knowledge about myself and where I stood that I could rebel against things I did not understand. It didn’t lead to any tension but I grew up different and was able to see things a lot easier. My identity has the biggest impact on my hospitality and appreciation. It is all about respect for other people, and I have a lot of that.

Despite Kamaka being part native Hawaiian herself, she has had experiences in which she had been discriminated against under the assumption that she was not Hawaiian. In the summers of her high school career, Kamaka would meet for water polo practice at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama High School, a school that served students that were accepted and could prove they had Hawaiian blood.

A lot of the players were brown. The first day I came, I noticed I was lighter than everyone else. I was swimming around the pool and some players were talking about using the gym before pool practice. I asked if I was allowed to join even though I did not go to school there. A boy responded, “No, it is for Hawaiians only.” And everyone started laughing. At that point, I felt so ashamed of how I looked. I felt ashamed of being mixed race. I haven’t thought about it that much but it’s certainly something I remember and won’t forget.

As Kamaka became older, she grew proud and comfortable with the way she looked.

I have something from everybody. When people ask what races I am, I always start with sharing that I am Hawaiian, and part Asian, and then white. A lot of people do not believe me when I say I’m asian. I have a lot of influence from Asian members in my immediate family and hanai family. I am the most proud of my Hawaiian background because I grew up having to memorize my genealogy and am the most knowledgeable with that side. I am a little more disconnected with my Asian side because they came to the sugar plantations and had to leave their families so I have a hard time finding out where they are from.

As a server at the Cheesecake Factory in Waikiki, Kamaka the majority of people she serves are tourists, while at Aloha Beer Company, she serves more locals.

When I am working at Cheesecake I share the ethnicities that relates to who I am talking to. It’s kind of a marketing tactic because the majority of my coworkers do not know much about Asian cultures and are not from Hawaii themselves. I am proud of those cultures that I share and will know how to say at least one thing in those different languages. When I go up to a table, I look at their menu to see if it is in English, Chinese, Japanese or Korean. Sometimes I can even tell where they are from based on their clothing or mannerisms. I greet them in their native language then continue in English because I am not fluent in Japanese or Korean. The guests are usually impressed and I get more tips. If I start with saying “Konichiwa!” they are a lot more receptive and appreciate me. Everyone deserves to have their culture reached, especially here. Even if I do not have their blood in me, I try to learn their language a little. I love being able to connect with people in that way.

Kamaka wants to make all people feel welcomed, not just to the restaurants she works at, but to the island. Her kindness towards tourists is controversial because of the widespread tension with the tourism industry in Hawaii.

There are so many negative connotations amongst locals within certain outside groups coming for vacation and not giving back. I’m not saying it’s not merited but most people are not coming to negatively affect our land. They are coming here because of the way the islands were shown to them. I think I move gracefully in understanding differences across multiraciality because it makes people feel welcomed and perhaps makes them want to give back and learn about Hawaii’s identity and culture.

Kamaka has been able to connect with the history of her multiracial identity through ethnic studies in college. Through the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920, the federal government began sponsoring a homesteading program for native Hawaiians, defined as “any descendant of not less than one-half part of the blood of the races inhabiting the Hawaiian Islands previous to 1778.” This means you must have a blood quantum of at least 50% Hawaiian to qualify for the program. The Act stated that the State had an obligation to manage resources that would benefit native Hawaiians inhabiting the crown lands that were taken through colonization. However the homesteading program also served as a divide and conquer tactic to segregate native Hawaiians with a lower blood quantum who did not qualify for the program. Prior to the HHCA of 1920, native Hawaiians were accepting of interracial marriage and mixing because they were not concerned with preserving full-blood Hawaiians. They did not think their race would be wiped out.

Hawaiian people believed that if you were part Hawaiian, you were Hawaiian. The Act proved to be effective to this day because people still ask how much Hawaiian I am. Blood quantum has been effective in separating people and making more Hawaiian people condescending to those who are not as Hawaiian as them. I’m sad for those people who are territorial of their Hawaiian identity and hope they read and research to understand the true Hawaiian values. This behavior is not representative of Hawaiian people, but of tactics outsiders used to divide and conquer us.

Kamaka realizes her mixed race is a grounding force for her as a whole person. She likes being friends with everybody regardless of their race, but has discovered that she appreciates being friends with people who can share her mixed race experience. She’s become more introspective and aware that other than her siblings, there is no one else in the world who perceives race and culture in the same way she does. This has given her comfort knowing that welcoming diversity is the normal way of life in Hawaii.

Ikaika Rawlins

Ikaika Rawlins never imagined living anywhere else besides where he feels most fit and comfortable — in Hawaii.

Rawlins grew up with his brother and parents on Hawaiian Home Lands in Hilo speaking Hawaiian in the household. His mom taught Hawaiian language at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and helped launch Hawaiian immersion preschools through ‘Aha Pūnana Leo, an organization dedicated to reviving the Hawaiian language.

Rawlins has a quarter of Hawaiian blood from each of his parents and is also Irish, Chinese and Portuguese.

His mom being one of 12 children, Rawlins grew up with over 30 Hawaiian cousins from his maternal side of the family. “In a way I feel almost monocultural because I was always surrounded by Hawaiian kids,” laughed Rawlins.

“If you asked me how I identify, I’d identify as a Hawaiian trying to exist in a modern world,” said Rawlins. His multiraciality means he is more diverse and by extension, more open of a person. “If you value all your ethnicities and the cultures it relates to, you’re going to be more open, understanding and appreciative of different perspectives because you have all these other backgrounds going on.”

The second racial identity he most identifies with is Irish. Rawlins’ grandma was a practicing Catholic that would share stories with him about their Irish ancestors. “The Chinese side was never kind of brought up,” said Rawlins.

“In Hawaii, you are surrounded by so many people,” said Rawlins, “and it makes people want to learn more about you.”

Rawlins never thought about cultivating relationships with those of other races intentionally, but he thinks it is important.

“It was never that I needed my white friend to fill the white box, my Asian friend to fill the Asian box and my Black friend to fill the black box,” said Rawlins. The situations he has put himself in have allowed for a lot of interactions with diversity in his life.

“At my mom’s birthday party, it was the full rainbow of multiraciality. Tongan, Fijian, Black, white, Chinese, and Vietnamese,” shared Rawlins. From attending Kamehameha Schools Kapalama High School as a boarding student to UH law school to practicing law on Oahu, he has always encountered people from various walks of life.

Rawlins currently lives with his wife in an apartment in downtown Honolulu, near Chun Kerr LLP, where he works.

For Rawlins, living on Oahu has both fostered and inhibits multiracial interactions. “You’re around so many different ethnicities and you get bits and pieces everywhere,” he said.

Some cultural events and holidays celebrated by ethnic groups in Hawaii include Chinese New Year (China), Obon Festival (Japan) and Flores de Mayo (the Philippines).

“It also inhibits in a way because everything gets mashed up into local culture and it gets a little shallow sometimes,” said Rawlins. “You don’t get the depth of understanding someone’s deep culture.”

People come to Hawaii because it is a beautiful place and they want to have a good time, but not all locals have empathy toward Hawaii’s tourist population.

“I get why they want to come here,” said Rawlins, “but we need to do a better job regulating the industry.” Visitors spending money to stay in ocean view hotels and have private surf and paddling lessons are also accompanied by a jutting homeless population resting outside storefronts and tramping along beaches. “I think we should provide more programs for people at hiking and beach spots,” said Rawlins.

Like the tourism industry, real estate development is another controversial topic for locals living in Hawaii. Rawlins explained that the “anti” mindset of developing stems from the scar tissue trying to heal from impulsive developing back when Hawaii was first undergoing rapid industrialization.

To Rawlins, the underlying concern is not with development or development owners themselves but rather who is reaping the benefits from development. If more expansion plans were focused on creating affordable housing for locals and native Hawaiian residents, the people of Hawaii would be more enthusiastic.

As a lawyer who specializes in real estate and business transactions and tax planning, Rawlins hardly comes across native Hawaiians who require his service.

“I was helping a family that owned an entire ahupua’a that has been chopped up over the years in Punalu’u,” said Rawlins. The owned land with a care home of which half was owned by a family corporation and the other half was owned by a drug addicted cousin. “It was heartbreaking but I was able to help them get things cleared up on their corporate side and move in a more positive direction.”

He does a lot of volunteering to reduce the cost of his work as a way to give back to those going through hard times in his native Hawaiian community.

With regards to the historical impact of the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom and the more recent economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on locals and native Hawaiians, Rawlins thinks actively in terms of building Hawaii for Hawaii.

“There are ways to address that historical wrongdoing,” said Rawlins. “But a big part of how you heal as a people is, while you can’t ever forget, you can try to move forward in a productive way.”

Puamakamae DeSoto

Puamakamae DeSoto is a 17-year-old native Hawaiian professional surfer from Makaha. She is a nine-time national champion and full time student at Kamehameha Schools Kapalama High School.

DeSoto lives and breathes her Hawaiian identity in particular through her education, activism and surfing career. She also has Native American roots on her dad’s side and English roots on her mom’s. Her multiracial identity gives her the opportunity to learn about her family’s and others’ cultures. “It allows us to sometimes feel uncomfortable,” said DeSoto.

When the Hawaiian language was made illegal in 1896, DeSoto’s grandma relegalized the language by going door to door to have people sign to support five different laws. “It has become my kuleana to carry that and shine the light on my culture and be proud of who we are,” explained DeSoto.

kuleana – right, privilege, concern, responsibility, title, business, property, estate, portion, jurisdiction, authority, liability, claim, ownership, tenure, affair, province; reason, cause, function, justification.

“We have a unique culture that has been shut down and belittled so many times, so it’s special to be in a time to be growing the presence of our culture,” said DeSoto. “It’s amazing to see the growth we’ve had in the last ten years. I remember growing up and nobody could speak Hawaiian but now I meet people that are fluent.”

From teaching young kids how to grow traditional Hawaiian crops to chanting atop Mauna Loa to protest the Thirty Meter Telescope, DeSoto has been a powerful influence in preserving Hawaiian culture amidst widespread diversity in Hawaii.

“It has created a lot of struggles having multiracial Hawaii,” said DeSoto referring to gentrification. “The fact we have a ninth island in Las Vegas or Arizona or Texas is sad because that’s the only place where native Hawaiians can afford to follow their dreams.”

DeSoto believes that many youth from Hawaii choose to go to the mainland for college to be recognized and prepared for their future careers since the same opportunities are not prioritized within Hawaii. “Hawaii has become so touristy that locals do not get the attention they deserve,” said DeSoto. “It shows its priorities and the priorities, I think, are wrong.”

Through a multiracial lens, DeSoto applies the same standard for how to treat others — she treats people how she wants to be treated, but also treats people how they treat her.

On behalf of her native Hawaiian community, DeSoto shared that the interactions foreigners will have with locals and native Hawaiians when they visit Hawaii will depend on their respect and aloha. “If you are going to educate yourself and try to at least even read a two minute article about the history of Hawaii and be able to have that conversation, I feel like I cannot be respectful to you,” said DeSoto. She believes the same thing goes for Hawaii locals traveling out of the islands to other people’s homes.

“Sometimes you have to be the first person to be respectful and in Hawaii it’s hard for people to do that because it’s been internally demolished,” said DeSoto. “Even in a relationship you have to break boundaries yourself but in Hawaii it’s more about people breaking boundaries for us.”

DeSoto surfs all over the island, with her go-to spots being in Makaha and on Oahu’s north shore. Certain surf breaks are more localized than others and are dominated by native Hawaiians who have been surfing at those spots all their life.

When DeSoto’s dad was a young boy growing up in Makaha, he had to sit on the outside and wait until all the older generations of surfers on the inside caught waves. “They waited their whole life to have this opportunity so they get territorial over that because they are not used to change,” explained DeSoto.

DeSoto has observed that interracial tensions arise when one person paddles over feeling entitled to the waves. “When we surf, we are in our home… if you come with aloha, you’ll get aloha,” said DeSoto. “There are a few locals that have things going on in their life and will personally take it out on other people at every surf spot, just don’t engage when you drop in on the wrong person,” advised DeSoto.

Even as a native Hawaiian herself, DeSoto has been yelled at for the color of her skin and not looking or being Hawaiian enough, but her attachment to her own identity is stronger than anyone’s perception of it.

“I’ve been yelled at to go back to the mainland but there is no way around that because there are no full blood Hawaiians anymore,” said DeSoto. She continues to empathize with her Hawaiian identity because it has been abused so much.

DeSoto does not try to mediate when others are conflicting in the water and start to use their race as a right. “I hate pulling the native Hawaiian card — I don’t paddle around saying I’m native Hawaiian so you gotta respect me.” If she feels she has to, she’ll try to expel those who are territorial.

“It’s a haole way of life to be territorial,” exclaimed DeSoto. “It’s a Hawaii thing to shower people with love and aloha.”

DeSoto shared that she sometimes hesitates to talk about race, but finds that to talk about identity you have to be vulnerable. “I am still learning so much from people and I’m 17 so sometimes things come out wrong,” said DeSoto.

DeSoto continues to do her part to be the bridge between native Hawaiians and foreigners by educating herself and others on the true history and story of the Hawaii identity.

Terms in the Hawaiian language to describe different identities

hanai

foster child, adopted child; to raise, rear, feed, nourish, sustain; provider, caretaker.

In Hawaii, people often informally “adopt” people into their families and take care of others as if they were a blood related loved one

haole

White person, American, Englishman, Caucasian; American, English; formerly, any foreigner; foreign introduced.

hapa

1. portion, fragment, part, fraction, installment; to be partial, less. 2. Of mixed blood, person of mixed blood, as hapa Hawaii, part Hawaiian.

hapa haole

Part-white person; of part-white blood; part white and part Hawaiian, as an individual or phenomenon.

kama’aina

Native-born, one born in a place, host; native plant; acquainted, familiar, land child.

kanaka maoli

Full-blooded Hawaiian person.